|

||||||

| Magazine | Advertising | Calendar | LA Screenings | Archives | Newsletters | Contact Us |

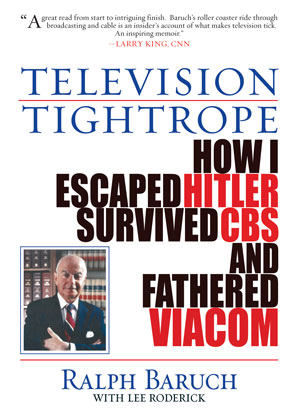

Ralph Baruch’s Book: The Bad, the Good and The UglyBy Dom Serafini I first met Ralph Baruch in 1979, as the international editor for TV/Radio Age. The publisher, Sol Paul, who considered Baruch a legend, arranged my visit to Viacom’s offices in Manhattan. Baruch had helped found the media company and served as its CEO.  At 56, he was two years older than my father and appeared as one can see him now on the cover of his new book, “Television Tightrope: How I Escaped Hitler, Survived CBS and Fathered Viacom.” Even looking at the various old photos that illustrate the book, it’s amazing how he’s barely changed. Despite the “legendary” aura surrounding him, in preparation for the meeting, Paul could only say that Baruch spoke various languages, that he had escaped the Nazis and that he was “tough.” Being thrown in the lion’s den was a normal occurrence for editors at TV/Radio Age, especially when its sales director, Mort Miller, had to get ads. Coming from an engineering background helped in the sense that I only got anxious when interviewing such luminaries as Vladimir Zworykin or Peter Goldmark. However, Baruch had come from CBS and, therefore, had worked closely with its founder, William S. Paley. That fact by itself was awesome. Together with David Sarnoff and Leonard Goldenson, Paley was, in my mind, as one of the Olympus Gods of television. Not being able to approach him, nine years earlier, I would drive a yellow Beetle in front of Paley’s Long Island’s estate at the risk of being arrested for trespassing, just to feel “near” him. Today, reading through Ralph Baruch’s 366-page book (published by Los Angeles-based Probitas Press), one discovers that he too came from an engineering background, having, in 1943, taken a job as a recording engineer after learning from a technical book loaned to him by a friend who could afford to take the classes. This made him appreciate scientists such as Zworykin, defined in his book as a “prolific genius;” and Goldmark whom he called, “the brilliant CBS resident inventor.” Baruch also admired Sarnoff, Goldenson and, especially, Paley. About the time I was trespassing on the CBS chairman’s property, Baruch was having lunch with Paley to talk about Viacom. The 70-year-old Paley was running 45 minutes late. This is how the event is described in the book: “The thin beef steaks … were cooked to be eaten at 1:15 and were served 45 minutes late…. I tried mightily to cut into the shoe leather-tough meat using proper etiquette. No luck. Finally I pinned a piece with the knife and was able to pierce it, then tried by sheer force to separate it from the rest of the steak. Suddenly it skipped across my plate and across the table like a Frisbee, landing near Paley. I thought it was funny. He did not…He threw a disparaging glance my way and did not talk to me the rest of the luncheon.” Indeed, it is a funny vignette, but it is hard to imagine Baruch, even at age 48, actually laughing. Unreal as it seems, Baruch sprinkles the book with some funny anecdotes, like the time he told CBS president Frank Stanton he did not like the name “Viacom.” He also wrote that CBS executives would ask him his opinion on a show’s chance for success. If he liked it, they considered the project a failure, if, on the other hand, he disliked it, it was considered a winner. According to Baruch, being successful in television is “never underestimating the public’s bad taste.” Indeed, he can be very critical of television, commenting that reality shows prove just how uncivilized people can be. He also describes, feeling “trapped in Tinseltown.” He is at his best, however, when he describes (here paraphrased) how Viacom came about: “So, here was the deal: I was to lead a brand-new company whose board I did not know… with an oppressive contract dictated by CBS, with a number of executives cast off by CBS, an outside law firm in which I had no confidence, a costly employee benefits plan, an expensive lawsuit hanging over and a forfeited microwave license to connect many of our cable systems.” In later years, Ralph and I would casually meet at a luncheonette on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, but he never ventured into personal stories. Despite the fact that — as Sumner Redstone, the new owner of Viacom, wrote in his book, “A Passion To Win,” –– when Baruch departed, he was “well provided for,” Ralph and his second wife Jean (to whom his book, as well as a full chapter, are dedicated) would enjoy simple things such as sitting at the counter for breakfast in a greasy spoon coffee shop. It was known that on domestic flights, Ralph liked to fly economy. So, when his Viacom executives who managed to get upgraded on the return flight from TV trade shows, such as NATPE, would spot him on the plane, they rushed to get downgraded. It’s not as if

he’d never known any better. Before losing

everything to the Nazis, he lived in relative wealth, in Frankfurt,

Germany with his father, an international lawyer who had also studied

at Oxford. Arriving in America destitute, and with both parents in poor health, Baruch worked in a shoe factory bringing home $14 per week. When, in 1943, Ralph took the sound recording job, he felt he could afford to secretly marry his 17-year-old girlfriend, Lilo, whom he had met a year earlier. They were both Jewish refugees from Frankfurt, where Lilo’s father had been a medical doctor and both had narrowly escaped the Holocaust. Baruch describes this new phase of his life: “We both belonged to dysfunctional families. My parents had a bad marriage and so did hers… When [the marriage became known] both sets of parents protested vigorously… Her parents’ unyielding objections broke Lilo’s heart and foreshadowed the depression that would visit her periodically.” The most dramatic part of the book, however, is when Baruch describes his odyssey, which began at the age of nine, after his father was arrested by the Nazis and was able to escape. The whole family –– mother, father, Ralph and older brother Charles (who later died) –– escaped from Germany to Paris, France, where he had to learn a new language and go to school. At the age of 17, a few days before the Nazis were to take Paris, Ralph was able to convince the family to move to the Spanish border, with “just two suitcases –– one filled with family silver, money and jewelry, and the other with clothes and other personal items.” A relative in New York managed to get them “emergency visas” to enter the U.S., from the American Consulate in Marseille, but they could not leave from that port because the French required “exit visas.” The French had to report all applicants to the Nazis, and Ralph’s father was wanted as a spy. Instead, they obtained Spanish and Portuguese transit visas and by foot, bus and car snuck out of France through the Pyrenees Mountains to board, in late November, the Nyassa from Lisbon, bound for New York. Ralph wound up at CBS

in 1954 by first going through the DuMont TV Network, which he joined

in 1950 as a TV spot salesman (after a stint selling music licenses

to radio stations). When

he joined CBS Films to sell programs to nearby TV stations, Ralph

had three daughters: Eve, 10; Renee, six, and Alice, three. In 1959,

just before becoming the head of CBS Worldwide Distribution, his

wife Lilo died, a year after giving birth to their fourth daughter,

Michele. At this point, the book slows down and for the next 40 pages, it becomes a TV history report with chapters such as: “Early Television,” “DuMont and CBS” and “The Tiffany Network.” But even in those slow-turning pages, one can capture, here and there, some unusual or socially valuable fact. For example, when Allen DuMont asked Ted Bergmann to become the new head of his network, Bergmann commented that, “Our business depends on sales to advertising agencies…[and] most ad agencies don’t like to do business with Jews, and this may make it difficult for us to work with these agencies.” To that DuMont replied: “If that’s the way they feel, then I don’t want their business anyway.” On the following page, Ralph reported, “Pope Pius XII announced that Saint Claire of Assisi was the patron saint of television. Placing an icon of her on the TV set was said to improve reception.” The book picks up again in Chapter Seven (“Selling CBS Across the Globe”) but the pace is spotty. It moves well, for example, when Baruch describes his relationship with various international broadcasters and when he goes back to personal anecdotes. It’s not clear for whom the book was intended. It has too much industry jargon (e.g., “…agreed to do it on spec”) to be for the general public, and too many known facts to be for industry insiders. It is possible, however, that the book is just an instrument to set the record straight. Some people in the industry (including this reviewer) feel Baruch’s achievements have not received their proper place in history. Redstone’s book, for example, devotes just nine lines to Baruch. The Museum of Broadcast Communications’ “Encyclopedia of Television,” completely omits Baruch, even though it lists people such as John Bassett of Canada’s CTFO. Ironically, the Museum’s founder and president is Bruce DuMont, a nephew of Allen, under whom Ralph worked. In Les Brown’s “Encyclopedia of Television,” Baruch’s entry takes only 11 lines, fewer than the late Henry Gillespie, who worked at Viacom, but was not even mentioned in Ralph’s book. Nonetheless, Baruch’s book is especially interesting for what it omits. Even though the book is encyclopedic, with over 300 people named, it neglects many others, and brushes aside with one or two lines factors that one has reason to believe were important to him. Take, for instance, the International Academy, to which he devoted only 22 lines, of which a few are critical: “Concerned about possible proliferation of Emmys, we restricted the awards to two categories: Fiction and Non-Fiction. (Fears of proliferation were well-founded: The International Emmys now consist of 14 categories and four special awards.)” Baruch co-founded the International Academy together with NBC’s Ted Cott –– someone who had previously offered him a job that he refused –– and, later on, was helped by Renato M. Pachetti of Italy’s RAI. Here, there are a few discrepancies. Baruch wrote that the first International Academy Emmy awards gala ceremony was held in 1963, but in1985’s VideoAge International Council Membership Directory, contributing editor Ken Carlton, wrote that the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, which owned the Emmy logo, chartered the Council in 1968. Ken Carlton is the son of the Council’s first executive director, Richard Carlton, who was hired by Baruch and Pachetti in 1983 (before that, it functioned as a voluntary organization). Then, in VideoAge’s 1991 Salute to Pachetti, he told the reporter that the organization was started in 1967. In 1975, Pachetti was nominated chairman. Nonetheless, neither Carlton nor Pachetti is ever mentioned in the book, which is strange, especially in Pachetti’s case and considering the attention Baruch devotes to other international broadcasters. The RAI executive first met Ralph in Rome in 1959 and when Pachetti was transferred to New York a year later, they became good friends. Pachetti hired Ralph’s daughter Michele to work at RAI in New York in 1983, and also arranged for the Baruchs’ visit with Pope John Paul II in 1986. A photo included in the book captures this visit. Baruch is one of the founders and major supporters of the Academy’s Pachetti Memorial Scholarship, instituted after Pachetti died in 2003. The two were so close that when Pachetti was upset with something VideoAge published,

Baruch would ignore me too. Nevertheless, in the late ’80s

Pachetti and Baruch arranged to change the Academy’s by-laws

so that the organization would accept me as a member (before that

journalists were not allowed as members), and, in 1990, Gillian Rose

left as VideoAge’s editorial director in London to

join the Academy as program manager. His insight is also legendary. During a speech in 1988 he said: “The cable industry needs to pay more attention to Main Street than Wall Street…. Wall Street can’t be trusted.” In the same speech he also commented that “Broadcasters aren’t the cable enemy, the Telcos are.” The fact that, at times, Baruch

would be displeased did not bother me, since that was part of the

reporting job. He was not the only one. For a while, Haim Saban stopped

advertising with VideoAge because of something we wrote about his

early life in Israel. Bert H. Cohen of Worldvision, for example,

would instruct his advertising manager not to place an ad facing

the “My 2¢” editorial

page, because he was afraid that its controversial nature would put

his potential clients in a negative mood, affecting the way the ad

was received. Unfortunately, Ralph’s book explains little about this development, mentioning neither Worldvision nor where NBC syndication business went. However, the book does mention something else not found in any other reference books: The creation on the part of the three U.S. TV networks in 1959 of the Television Program Export Association, to press for open markets abroad. Besides Gillespie, other prominent Viacom people left out of the book are Larry E. Gershman, J. Brian McGrath, Norman Horowitz, Henry Schleif and Jim Marrinan. The late Gillespie started as president of Viacom Enterprises and became chairman of Turner Program Services. Gershman was hired by Baruch and became president of MGM/UA TV Distribution. After Viacom, McGrath became president of Columbia Pictures International Television. Marrinan became president of ITC. On the other hand, in the book, my name is mentioned as a minor contributor. Curiously, after they left Viacom, most of the aforementioned people became strong supporters of VideoAge from day one. On the other hand, Viacom people mentioned in Baruch’s book, such as Willard Block, Ken Page, Fred Gilson, Howard Karshan and Gerry Laybourne were not. Including Baruch. This is because those “old timers” (as we like to call them despite being warned not to by Horowitz), together with others such as Don L. Taffner, Bruce Gyngell, Len Mauger and Charles McGregor, may not have forgiven me for leaving their friend Sol Paul at TV/Radio Age, not knowing, perhaps, that Paul refused to become a partner in VideoAge. Later, Paul’s venerable bi-weekly fell victim of a left-ended maneuver orchestrated by the publisher of a major trade group, and VideoAge was the only publication to feature a tribute to him after his death. Years later, Horowitz (now one of our columnists) explained that, when he replaced Gershman at MGM, he did not have a budget for ads, having to worry about meeting payrolls. Gyngell became courteous even driving me around his hometown of Sydney. Years later, with Raul Lefcovich as head of its international sales, Viacom started to support VideoAge when, in 1983 it started covering the L.A. Screenings (a name that VideoAge changed from the May Screenings). The late Lefcovich, who spent a good part of his career at Viacom is also absent from the book. Two other parts of Baruch’s book could be of interest to industry people: The part in which he comments on various international broadcasters, and the chapter in which Viacom’s CEO, Terry Elkes, told him: “Ralph, you’re dead meat.” Baruch started to meet international

broadcasters in 1959, visiting Australia’s Frank Packer (Kerry’s

father) and Rupert Murdoch. In 1963 he helped break the Packer-inspired

buying pool undetected by Packer’s spies. In Germany, where he returned to for the first time in 1953, he became friends with Dieter Stolte, who was later named director general of ZDF, the country’s second TV network. Baruch wondered, “Why would anyone call their enterprise number two?” In Japan he

worked with TBS’s Junzo Imamichi, whom he admired. In

Canada, Baruch started working with the CBC, “In the spring

of 1962 [when CBC’s Doug Nixon] arrived in Los Angeles to preview

new programs offered by the Hollywood studios and the networks.” It

was in effect, the L.A. Screenings, which, however, according to

Jack Singer, considered the event’s father, started in 1964. What seems to have impressed Baruch the most, was dealing with Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, possibly because, as he writes: “By 1987 Italian television imported $300 million worth of foreign programs, nearly half the European total of $675 million.” That particular relationship would not have been appreciated by his friend Pachetti, who during PrixItalia, together with other RAI executives, would go around the hotels trashing copies of VideoAge with its fifth anniversary salute to Berlusconi’s Canale 5. Baruch had once attended the RAI-sponsored PrixItalia TV Festival as Pachetti’s guest. The “Ralph, You’re Dead Meat” chapter is a tirade against Elkes and various descriptions on how Viacom fought corporate “pirates,” such as Carl C. Icahn. Sumner Redstone’s book, “A Passion to Win,” best summarizes Baruch’s fights with Terry Elkes: “…Baruch and I had formed a relationship, in part because he couldn’t stand the rest of the management team. Why? One of the reasons was that despite having had a lot to do with Elkes becoming CEO of Viacom, Baruch had been left out of the planning for the LBO.” Baruch wrote: “Elkes […] planned to do a leverage buyout of Viacom, using the assets of the company to raise the funds. [Elkes told him] Ralph… I have formed a group of insiders and you are not part of it…. You should realize ….you are dead meat.” Redstone entered the picture. He had been waiting “in the wings” and, ultimately, in 1987, he bid $55.50 a share, $15 more than Elkes’ original offer, and thus was able to acquire most of Viacom’s stock. At that point, Ralph was offered office space and an efficient secretary, “and I moved into a nice corner office there on July 28, 1987,” because, as he wrote earlier: “I choose to wear out rather than rust out.” |

||

© 2008 Video Age International |

||